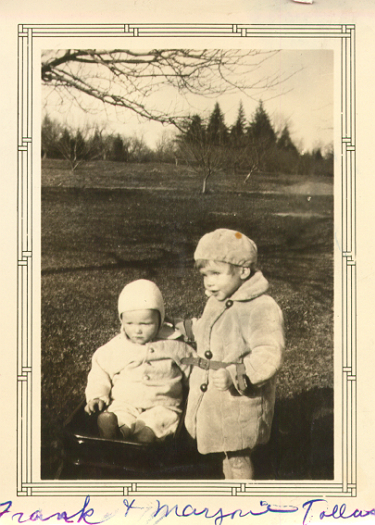

Our First Homeplace – Margie (Tollas) Bernard

“Smell is a potent wizard that transports you across thousands of miles and all the years you have lived.” -Helen Keller

Whenever I get a whiff of boxwood, daffodils, curry spices, or geraniums I find myself transported back to my childhood home in Michigan. These odors, individually or separately, recall the boxwood hedge surrounding the manor house at Hadleigh Hill Farm in Royalton Township, Berrien County. One field was carpeted with yellow daffodils in spring; its kitchen contained pantry shelves filled with exotic spices; the woodsy odor of geraniums transport me to the four-room cottage where I lived with my parents and brothers Frank, Bob, Calvin, Phil and for a few months in 1944, Chuck.

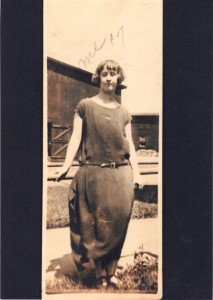

My Mom and Dad, Alfred & Lena (Barker) Tollas, married 23 May 1931 during the height of the Great Depression; he was 27, she 23. The ceremony was performed by Rev. F. C. Schmidt at the Zion Evangelical Church in St. Joseph, Berrien County, Michigan. Their witnesses were Mom’s brother Oscar Barker and his wife Dorothy. Their marriage license state that Dad’s occupation was landscaping and Mom’s was factory work. They were hyphenated Americans, Dad first-generation Pommern-Prussian; Mom, third generation Irish.

They both had attended high school and Dad earned a degree in architectural drafting from the Chicago Technical College. (‘Diploma’ was the first word I learned to spell due to frequently staring at his graduation certificate on the wall next to the day-bed where I slept in our combined dinning-living room.) However, he never worked at his chosen profession; the Wall Street Crash of 1929 resulted in few requests for construction blueprints during the dim, dark, work-less years of the depression. Instead, he located a position as the gardener and general handyman on William Woodbridge Dickenson’s Hadleigh Hill Farm estate.

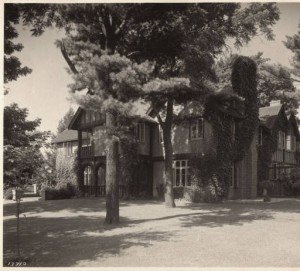

WW (as Mom referred to Dickenson) made his fortune as co-founder of the Marquette Cement Factory in Chicago, Illinois just across Lake Michigan from his estate in Michigan. There his imposing manor was situated on the St. Joseph River that ran between the twin cities of Benton Harbor/St. Joseph in Berrien County.

In addition to the manor, there were stables for horses, milking sheds for cows, a carpentry shop, and a hay barn that housed chicken coops. These buildings formed a U-shaped compound where, at the left front end, was a small dwelling in which lived Mrs. Hayhurst, WW’s housekeeper, and her son Johnny.

At the back of the manor-house a lawn slopped down to the river. On one side was an enclosed English flower garden with a greenhouse that was heated in the winter, and on the other a fenced-in tennis court. The front yard was hedged by boxwood bushes kept well-trimmed by Dad. He also maintained the estate’s vegetable garden, flower garden and greenhouse, fed and milked the cows and tended the horses.

With the help of Albert, the day-worker, Dad harrowed the fields with a horse-drawn plough, then planted field-corn and hay to feed the animals in winter. They shoveled out the manure from the barns to add to a compost heap used to fertilize the fields. They pruned the apple, pear, peach orchards; sprayed them with sulfur to prevent insect damage; then harvested their fruit in the fall. In his spare time, Dad repaired farm equipment and did carpentry work. In exchange for his labor, Dickenson provided Dad with a two-bedroom cottage and garden plot to house and feed his expanding family. Although I suspect Dad’s wages were slight, he managed to save enough to buy a Ford.

The cottage had no central heating, indoor toilet or running water. On the kitchen counter a water pump located over the sink had to be primed before water could be pulled from a cistern that gathered its contents from both heaven and earth. There was a Stanley Range cooker for cooking, baking and heating water that filled a large, round tin tub on Friday night for my brothers and my weekly bath; being the only female, I was first to get plunked into the freshly heated water. There was also a storage pantry off the kitchen and it was in this pantry I exhibited my first act of culinary preference and independence.

Except for being an excellent baker of bread, cakes and pies Mom wasn’t a good cook. One morning, I refused to eat yet another bowl of scorched porridge. After about ten minutes trying to coax me to eat, she put me and the bowl of porridge into the pantry, closed the door saying, “When you finish your breakfast, you can come out.” I stayed there hours until she finally relented and released me; the porridge uneaten.

Just before the double Dutch doors between the kitchen and dining/living room another door opened unto a stairway that led down to the basement where there was a coal storage bin sectioned off underneath a small window. In the fall, the coal man would insert a tin ramp from his truck down which thundered our winter supply of coal. The basement had shelves along two sides to hold the canned fruits and vegetables that my mother preserved from our garden and the farm’s orchards to take us through the long, cold, snowy winters. There were also bins for storing potatoes and other root vegetables.

The cottage window sills were always filled with pots of geraniums my father brought home from the greenhouse. I was given the task of keeping them watered and pruned of dead leaves. Sometimes in haste I broke off a still green leaf and its smell reminded me of newly plowed earth. Their blossoms were various shades of red and pink and when the plants died my father would bring home more.

A small entry room off the kitchen, where we removed our boots and hung our coats, led to the back yard. At the left of the house was our vegetable garden; beyond that an apple orchard. Once a tornado took out nearly a row of these trees, luckily missing our cottage. Our back yard had a storage shed that contained a chicken coop whose hens provided eggs and an occasional roast chicken dinner. There was also a pigsty whose pigs were slaughtered in the spring to provide us ham, sausage, head cheese and souse. Our milk came from the estates’ herd of cows and we churned our own butter. In summer, an icebox holding a block of ice kept perishables fresh; in the cold winter-months this was not needed.

An outdoor toilet off the back-yard provided we youngsters one memorable occasion of adult folly: Mom and Dad hosted a New Year’s Eve party attended by aunts and uncles who were seeing in the New Year and sending off to WWII, William and Victor Barker, my mother’s brothers. This was the only memory I have of alcohol ever being served in our house, perhaps due to the story told about Dad’s overindulgence that night which caused him to lose his dental plates down one of the toilet holes where he emptied the contents of his sick stomach the next morning.

The back yard also contained clothes lines that stretched between the cottage and the shed. In winter, our freshly washed laundry hung in stiff frozen lines until the faint sun thawed and eventually dried it which often took several days to accomplish.

The dirt road to our cottage from Dickenson Lane off the Niles Road that ended at St Joseph/Benton Harbor, was separated from our front yard by a hedge of spiraea which bloomed white in spring. In the middle of the yard was a tall elm tree on which hung a rope and board swing. The ground underneath the swing had a small indentation of bare earth attesting to its frequent use.

When I was born October 7, 1932, Mom & Dad were living on Nickerson Avenue in Benton Harbor and shortly afterward we moved to Hadleigh Hill. I was the eldest of what would become seven and one of my earliest memories was of cold Michigan winters spent sledding down a hill that ended at a large field which in spring became a carpet of yellow daffodils. The first time I read these lines: ‘I wander’d lonely as a cloud / That floats on high o’er vales and hills, / When all at once I saw a crowd, / A host, of golden daffodils / . . . .Ten thousand saw I at a glance, / Tossing their heads in sprightly dance’, from William Wordsworth’s poem The Daffodils, I immediately focused on my golden field where the sight of thousands of golden trumpets in bloom heralded the end of winter. Every year when I spot my first daffodil I bend down, close my eyes and inhale deeply of its scent to mark the beginning of another spring.

This daffodil field was met at its furthest edge by a small forest that contained a ravine which led to a sandy beach on the St. Joseph River where Dad frequently fished for bass and trout. This was also where my brothers and I learned to swim. In the forest grew wild grape vines which, Tarzan-like, we would grab onto and swing in an arc along the edge of the ravine.

In March 1934, I was christened at the Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church on Napier Avenue, St. Joseph by Rev. F. C. Schmidt.

Years later, I had my comeuppance at this same church when about eight or nine. That morning I and my brothers attended Sunday School in the basement of the church while our parents were at that morning’s sermon upstairs. Our session ended and while waiting for our patents fetch us, I circled my arms around a post in the center of the room and began swinging around it faster and faster. Just as our teacher tried to stop me, I lost my grip and slammed onto the floor. When I fell my teeth clamped down on my tongue causing a gash which began to bleed profusely. I was rushed to the local hospital emergency room where the gash was sutured; however, afterward my tongue began to swell preventing me fully closing my mouth or chewing food. I was put on a liquid diet of juice and eggnog until my tongue healed. This was doubly aggravating occurring as it did just before our annual Thanksgiving dinner; instead of eating turkey dinner with all its trimmings, I was appeased with numerous helpings of chocolate pudding and ice cream.

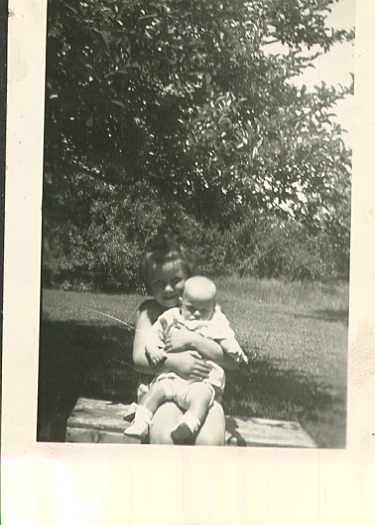

Every noon, Dad came home for lunch. Just before he arrived Mom would send Frank, Bob, Calvin and me into the dining/living room, latching the bottom Dutch door between it and the kitchen to keep us out of her way. With the top door open, she could keep an eye on us while she prepared lunch. One day, when he came home, Dad opened the bottom door but didn’t immediately latch it shut. Calvin, who was nearly two, toddled after him and before he could be stopped, tugged on the electric cord attached to the coffee pot and its contents poured over him.

I had just turned six, and although this was a most traumatic event for a six-year-old to witness, my only memory of that day is of my mother holding Calvin on her lap wrapped in a white sheet while she rocked him back and forth in the wooden rocking chair. Calvin died the next day. After his funeral at the Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church, Calvin was buried in the family plot at Riverview Cemetery in St. Joseph.

I, and when they were old enough, Frank and Bob, attended Royalton Elementary School, a two-room building located one-and-one-half miles to which we walked every day from our cottage no matter what the weather. I started Kindergarten just after I turned five in October 1937. Mrs Bussie was my teacher. One room was used as a classroom, the second served as a recreation room in winter when play outdoors was prohibited by snow several feet deep and nose-pinching cold. With the exception of the one year my cousin Beverly Krause lived in the area and joined me, I was the only person in my class for the six-years I attended, so I was both the best and worst student in my grade. What made this all-grade classroom unique was if I failed to learn a concept one year, it was made available to me when the teacher was explaining it to those in the year behind me.

One summer afternoon, after I learned to write the alphabet, my mother made me take a nap on her and Dad’s bed. I wasn’t tired, so to pass the time until she let me out, I took a safety-pin and diligently and proudly scratched the entire alphabet, in capital letters, across the solid walnut headboard. Mom was not pleased with evidence of my newly acquired skill.

Our school was a sturdy brick building that years later I learned WW, in a spirit of noblesse obliges, had had built to educate young people in the area. The main classroom had tall windows lining one side, a cloakroom the other. On the sill of one window was a pencil sharpener where I often stood sharpening pencils while gazing out the window daydreaming. A door at the far end of the room led to an anti-room that contained a furnace. At the back of the classroom, a door led to a hall with toilets on each end, one for boys and one for girls that contained the first flush toilets I’d ever seen.

One day when I was having difficulty learning to spell ‘February’, Mrs. Martin made me sit alone in the furnace room until I memorized it. About five minutes later I became bored so opened the back door, left, and walked home. Later that day, Mrs. Martin drove to our house looking for me which proved to be quite embarrassing because the incident was repeatedly told by Mom to numerous relatives while I stood squirming at the revelation of my inability to spell.

When I was eight, I was hired to work in the manor house kitchen; taught how to scour stainless-steel sinks using Bon Ami powder with a damp cloth then polished spotless with a soft towel. The kitchen smelled of a strange spice which, the first time I ate at an Indian restaurant in Washington, D.C. some thirty-years later, I realized were curry spices. I earned five cents an hour learning to make the sinks sparkle and I suspect initial training to eventually replace Mrs. Hayhurst when she retired.

This was the idyllic setting of my childhood. I looked upon the grounds, forest, river, tennis court, greenhouse, sledding hills, fields and animals as mine. My brothers and I never questioned our right to explore and enjoy this private playground. And, to my delight, there were always books to read which I would do endlessly into the night until it was too dark to see words on the page. I never gave second thought to whether we were rich or poor, there was always enough food to eat and adequate clothing to wear. However, my innocence about our financial and class status was to end with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on December 7, 1942.

We heard the news of the bombing while at Grandma Tollas’ home in St. Joseph celebrating my brother Bob’s sixth birthday. When I awoke the following morning, I felt a deep, unnamed fear grow in the pit of my stomach as I watched Mom and Dad huddled next to the radio listening to the news. The volume was so low I couldn’t make out what was being said but felt something terrible had happened to threaten my safe, secure world.

Shortly after my youngest brother, Chuck, was born in January 1944, the Tollas family home in St. Joseph was sold. When my father received his share, he showed us the four crisp $100 bills he’d received and I knew we were now wealthy! However, I soon learned the truth when in the spring of that year we were forced to pack our personal belongings and move from the estate. With the country at war, every able-bodied male was called upon to either join the military or work in an industry that aided the war effort. My father’s age and large family made him ineligible for the military and his work on the estate didn’t offer deferment, so he eventually obtained employment as night watchman at the Industrial Rubber Company in Benton Harbor. Because Dad could no longer attend to his duties at the estate, we were forced to vacate our home at Hadleigh Hill Farm.

We moved into a barn a few mines away that had recently housed animals. My father bought this place using his small inheritance as a down-payment. The farm had ten acres, mostly clay, rendering it useless to grow crops but then we had no equipment to farm with and no money to purchase what was needed. The barn consisted of one room that was two stories high sited beside a creek that frequently flooded preventing us from reaching the main road that led into the small town of Eau Claire a mile away. On the other side of the creek a natural spring provided drinking water we carried in buckets to the house

We moved with little more than our clothes, kitchen-ware and bedding to sleep on. The furniture in our former cottage belonged to WW and it took quite some time to buy replacements. Our new home had recently housed animals from the adjacent farm and smelled of manure combined with the peculiar odor of bedbugs that were its long-term residents. Their blood-filled bodies had a smell that haunted me for years.

Endnote: Although she never lived there, my sister Carol (Tollas) Knapp, a correspondent for the St. Joseph/Benton-Harbor Harold-Palladium, wrote an article in the 1900s about the demise of Hadleigh Hill Farm. She reported that several years earlier, the manor house had burnt to the ground and untended the land returned to its former wild state of hardwood and pine tree forests, overgrown brush and wild grass. However, she related that the estate had recently been bought by two developers and renamed River Trace Estates. The site was being turned into a luxury urban development of 39 one-acre lots priced from $45,000 to $115,000 each.

Published: 04/19/2016